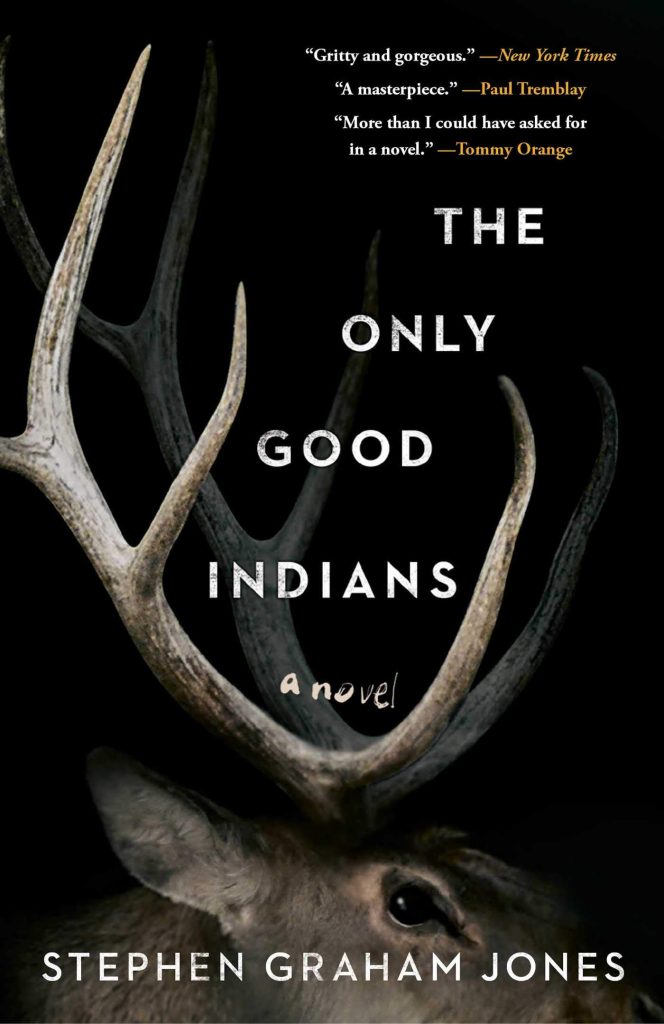

This past month, I (Selena Middleton, Stelliform Publisher and EIC) read Stephen Graham Jones’s The Only Good Indians alongside my friend and invaluable Stelliform helper and fellow English PhD, Kristen Shaw. Since our conversations often fall into fairly nerdy literary analysis, we thought we would share our thoughts about The Only Good Indians in the form of the conversation that we might have had if the pandemic had not prevented an in-person meeting. What follows is our conversation-review of SGJ’s novel, which was published by Saga Press in July 2020.

Both Kristen and I are settlers and our perspectives on the novel are shaped by that as well as our PhD-level training in literary analysis and various cultural theories — and reading as many books by Indigenous authors as we can get our hands on.

The Only Good Indians’ Slasher Roots

SM: Let’s start by talking about what this book is doing — riffing off of 80s or 90s slasher films. The book follows that format pretty closely. It starts with an establishing kill; I think it was Ricky in the parking lot? Introducing us to the elk and the social issues that Indigenous people experience in this town. I was pretty hooked by that opening, the way that I couldn’t tell as a reader which was more dangerous, the guys from the bar or the herd of elk that seemed just outside one’s periphery.

KS: Yes, that was a great intro. My mind went, “potentially supernatural killer elk? I’m in.” I found the whole book very cinematic and that initial scene really grasped my interest. It sets the tone but also introduces some social commentary about masculinity and Indigenous identity that will run through the novel.

In some areas the novel really shines in its riffing on slasher tropes, but it also subverts those same tropes in interesting ways. It also pulled out some of the tensions that are inherent in slasher stories but are not always explicitly acknowledged. For example, it’s common in slashers for the villain to be motivated by revenge. The villain might get a back story with some trauma that made them the way they are, which invites empathy from the viewer. In that way, I find horror takes advantage of a certain ambiguity in terms of the viewer’s relationship to the villain. They’re usually tragic figures, but they’re also killers — where should we place our allegiance? Who is the ‘real’ victim? The Only Good Indians definitely takes advantage of this ambiguity and pulls it out more explicitly than many more traditional slashers do, I think. There are so many shades of grey here. I found myself rooting for Elk Head Woman most of the time but also each one of the four central male protagonists because they are all oppressed by the systems around them and grappling with their own demons at the same time.

SM: Yes, I found my allegiance to various characters throughout the book on pretty shaky ground and I think SGJ plays with that a bit. He depicts Lewis, for example, as really sympathetic at first but he ends up being responsible for some really horrific stuff. For me, and I think a lot of other fans of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, Lewis is pretty relatable. He’s a reader, he immerses himself deeply in his fantasy books; but that’s what gets away from him in the end. Doing what he does — and I won’t go into the details but I thought Lewis’ actions were probably the worst and most gruesome in the book — he fully expects to find evidence of something monstrous, and in that to be justified in his actions. It seemed like a failure of imagination — not under but over-imagining. But at the same time, Lewis is under a lot of stress (being separated from his community and we get a taste of that stress of isolation in the scene where the police come to talk to him about his dog). I did get a sense — and I think a lot of us are hyper aware of the dangerous possibilities of police encounters now, if we weren’t before — that Lewis had experienced police harassment before.

So without giving away too much of the story, can we talk about Lewis’ actions, or the effect of them on the story? The effect of them on the reader? How they converge or diverge from horror tropes?

Violence Against Women and the Female Monster

KS: Yes, Lewis’ actions really shook me — I was truly not expecting the story to go in the direction it did. Violence against women is obviously quite prevalent in horror, speculative fiction, and culture generally, and it is a problem that many writers and creators have had to grapple with. My reading of Lewis’ actions are that they show how women ultimately pay the price for men’s own unaddressed traumas — perhaps even society’s repressed ills in general — and SGJ was trying to highlight that. While my initial response was disappointment that the story was rehashing the horror trope of violence against women, I started to interpret Lewis’ actions and how they fit into the novel’s social commentary differently after I finished the novel. I felt like Lewis was projecting his own guilt onto the women in his life to avoid taking responsibility for his past actions (in particular, the event that the whole novel centers around). Rather than confront the monstrosity in himself he projected that monstrosity onto the women close to him. I feel that the trope was used intentionally to draw attention to and critique the ways women (particularly Indigenous women and women of colour) are treated as disposable or as instrumental in the character development of men (in horror and in general). For me, my interpretation of this move was reinforced by the links that connect Elk Woman, Peta, Shaney, and even Denorah.

SM: I was also shocked and disappointed by the turn in Lewis’ story and the way the women around him get pulled into it. And I think you’re right about how this aspect of the narrative really underscores how women pay the price for systemic and unaddressed trauma. This part of the narrative was hard to take because I was reading it as part of the slasher arc — how certain kinds of women fall to the killer in a certain order. SGJ is definitely playing with that — the punishing of both the “too sexy” or “too confident” woman as well as the “good and faithful wife” (which I would put in a category with “the virgin” in slasher flicks — but I also think it’s important to note that here the “good wife” is a white woman and I think SGJ is probably criticizing the idea of white innocence).

But it’s shortly after this that the monster emerges as a character in the story–told in second person–and as I got to know what Elk Head Woman was about, and was further drawn into her concerns through the closeness of a second person narration, the horror I felt about Lewis’ actions started to change a bit. It’s subtle.

KS: Yes, the shift to second person that occurs changed my orientation to the story. It started to feel like Elk Head Woman’s story rather than the story of the four male protagonists. The use of second person increases the intimacy between the reader and Elk Head Woman, creating a connection between us that was not really cultivated as much between the reader and Lewis or Ricky at that point, at least in my reading. This was particularly interesting to me because horror doesn’t often humanize its villains, nor does horror have a great track record with women or even permit women to be villains. This occurs right after Lewis does some pretty horrible things, so the shift to second person — which creates the effect of a story being told to the reader from a woman/monster’s perspective — made me trust the narrative a bit more and consider how SGJ was exploring gender and its representation in horror rather than merely repeating the same violent tropes for shock value. It’s subtle and clever and puts the reader in a weird position where they have to negotiate their allegiances and commitment to certain character types. Clearly there is no singular or straightforward villain, nor are there any heroes, at least at this point.

Final Basketball Showdown

SM: Right, and when a kind of hero does emerge, it’s from a really unexpected place for a horror novel. I’m a bit annoyed that SGJ is making me talk about basketball, but let’s talk about basketball in the book. I started thinking about competitive sports as our modern version of war — this came through for me especially when SGJ describes the racist taunts that get thrown at the Native team. I suppose if you extend this metaphor then Denorah is a warrior and possibly the greatest warrior the Blackfeet have seen (at least in contemporary times). Denorah is a warrior, but she’s the one who stops the violence and it’s really cool to think of this as the responsibility of the warrior as well. Contrast this with the picture of a modern warrior that Lewis paints when he tells the story of the elk shoot that the four protagonists take part in. Four men heading out into the bush to bring back meat for the community is a pretty traditional set up; but they go where they’re not supposed to go, and end up wasting the lives and bodies of the elk in a pretty brutal and senseless way. When Denorah holds up her hand at the end of the book, it’s putting a stop to the violence of that original scene. That echo through history is really powerful. I kind of resent that it’s basketball that gets us there, but kudos to SGJ for making basketball relevant to someone who is not a fan.

KS: I’m not a basketball person either, so I’ll admit I’m not the intended audience for those parts. Despite my ignorance about basketball, I think that final confrontation on the court was really well-written and created a lot of tension. I love your point about competitive sports being a modern version of war. Traditionally both war and competitive sports are considered a masculine domain so it’s interesting to see that subverted here, as each of the women in the novel are described as skilled basketball players, and it is women who ultimately go head-to-head in the end rather than the typical final showdown between a male villain and final girl. Denorah holds up her hand at the end of the book putting a stop to the violence of the original scene, which again challenges the role of the final girl and traditional slasher conclusions, and she also subverts typical characterizations of women in horror as victims (virgin/whore) or damsels in distress. She breaks the pattern of violence and represents a kind of hybrid identity that doesn’t fall back onto stereotypes of femininity or seek to escape that by turning her into the cliche “strong” woman who just assumes traditionally masculine characteristics. Denorah for me represents a new kind of identity and a new kind of warrior. I was reminded of Grace Dillon’s concept of Indigenous futurism.

SM: Absolutely. I think SGJ is taking up this idea that Indigenous futures are always backward-facing. Challenging the idea that going back to the past and the way things were in the past, traditions as they were practiced in the past, is what an Indigneous future should look like. Here we get a future represented by a powerful, hybrid culture. A culture that forces questions about violence, gender roles, and what it means to be in relation with everyone and everything around you. That all of this is enfolded into a kind of oral storytelling style at the end is nice. It was a satisfying ending to a book that was sometimes really difficult.

4 thoughts on “Review: The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones”